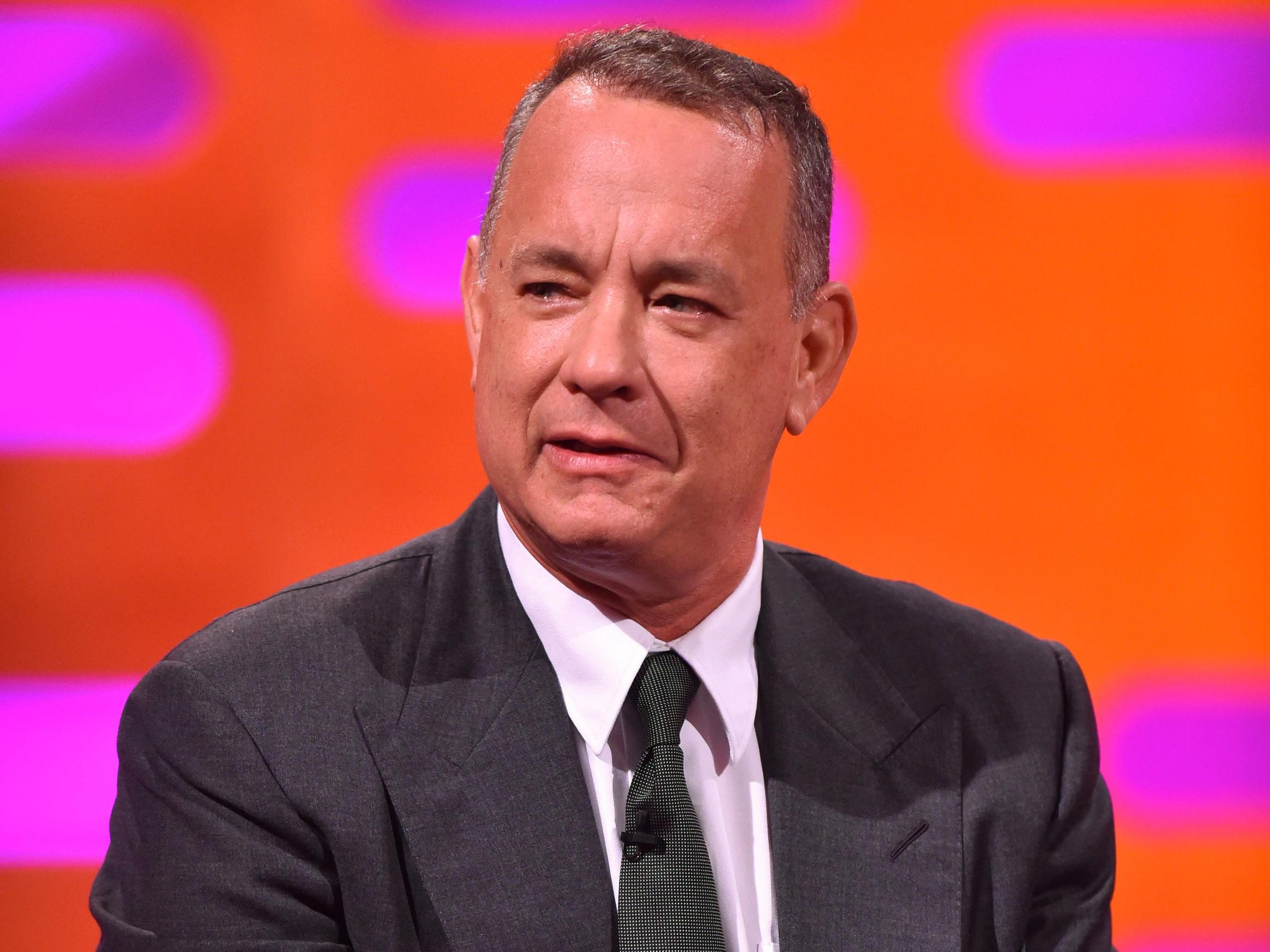

Tom Hanks on his debut book, Harvey Weinstein and Donald Trump

New book ‘Uncommon Type’ – a collection of 17 short stories – hopes to show that the two-time Oscar winner is as talented a writer as he is an actor

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In 2006, when Tom Hanks wanted to get a story published, he sent it to his friend and sometime director Nora Ephron.

Having had my own writing critiqued by her, I know just how daunting that could be.

“Oh, petrifying, horrifying, yes, yeah,” Tom Hanks says, grimacing.

The piece was a sweet paean to his make-up man Danny Striepeke, then 75 years old and retiring, a 50-year Hollywood veteran who had started by giving Elvis Presley his tan in Viva Las Vegas and Laurence Olivier his Roman nose in Spartacus and ended by turning Hanks into a policeman, an astronaut, an Army Ranger, an FBI agent, a Master of the Universe, a Slavic tourist stuck in an airport, Santa Claus and a Harvard professor of symbology.

Hanks sent Ephron the piece – “And she said, ‘Send it to The New York Times. I’ll make some calls for you. It shouldn’t be in the Sunday Styles section but maybe in the Thursday Styles section”,’ Hanks recalls. And after many rewrites and lots of no-mercy Nora editing, like “What does this mean?” and “This is not good” and “Voice, voice, voice” and “Tell people what you’re going to tell them, and then tell them, and then tell them what you just told them,” it was finally published in Thursday Styles.

I hesitate, wondering if now is the moment to break the news to Hanks: he has spent a decade honing his writing and, despite all the other acting and directing and producing he does, and despite being, as the historian Douglas Brinkley calls him, “American history’s highest-profile professor,” he has managed to squeeze in a book of fictional short stories called Uncommon Type. And yet he’s still going to be in Thursday Styles.

And not only that. I will have to ask him about the Times’s first bombshell report about Harvey Weinstein, published earlier this month, and Hollywood’s guilty silence on the incendiary subject. What does Mr Nice have to say about Mr Sleazy?

But the man is on a book tour, so first I needed to explore his fiction.

“Were you trying to be Chekhovian?” I ask.

“Boy, Chekhov just always goes right over my head,” he replies.

I confess that I don’t really know what that means, either, but a bookish friend had suggested I ask.

In profiles of Hanks, co-stars including Meg Ryan (You’ve Got Mail) and Sally Field (Forrest Gump) have made a point of saying that he is darker and more complicated and even more angry than you would imagine underneath that decent Everyman exterior, but he keeps it to himself.

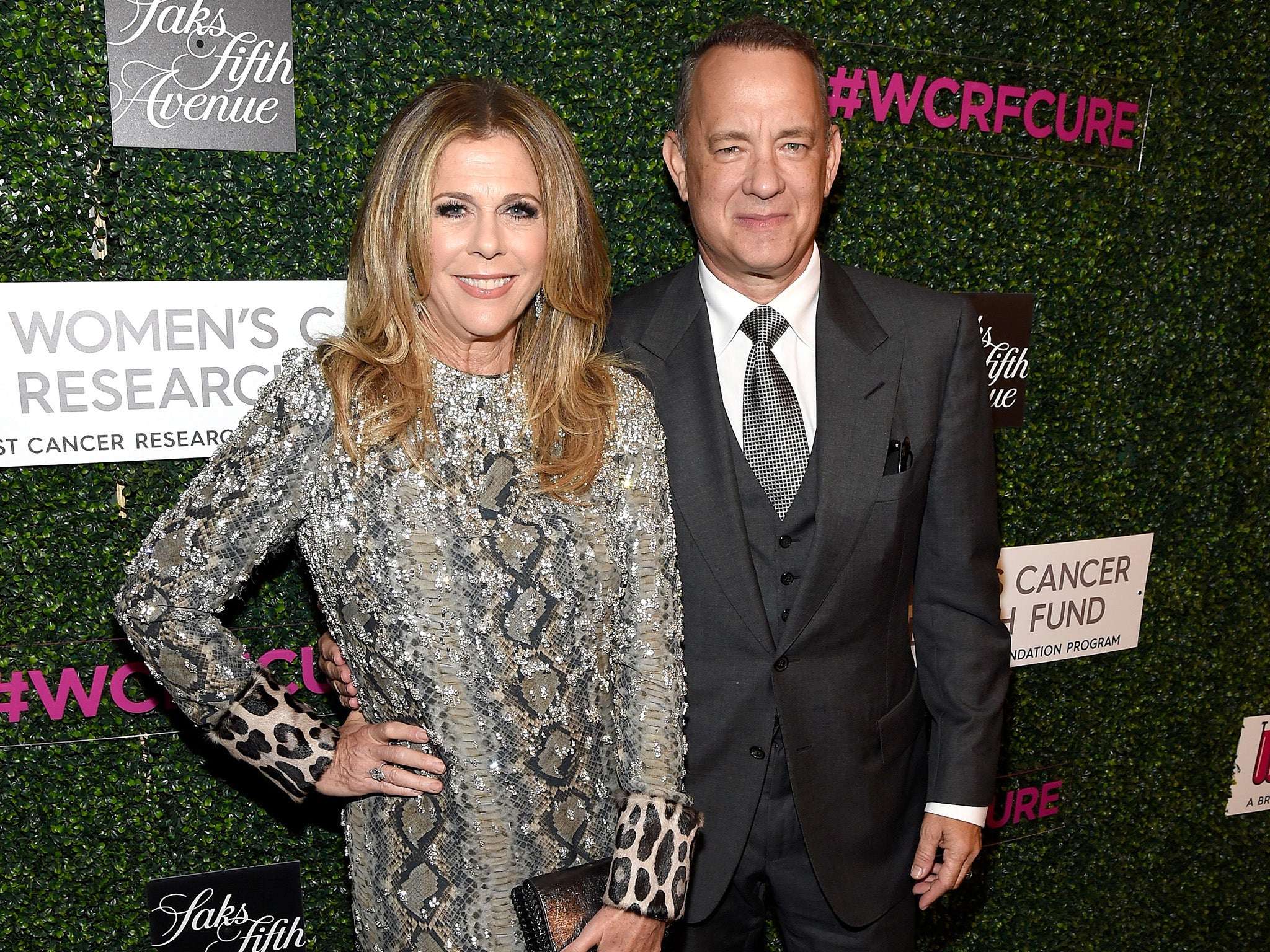

And it is interesting, given that Hanks and his wife, Rita Wilson, are celebrated as the king and queen of Hollywood, that there is a strain of melancholy that runs through many of the stories about small-town characters.

In one, A Special Weekend, a nine-year-old named Kenny is being raised by his moody father and brisk stepmother in a Northern California town – with a throng of siblings and stepsiblings – because his mother, a pretty waitress, broke up with his father when Kenny was little. He gets to spend a birthday weekend with his mother, who arrives in a cloud of perfume, with red lipstick that matches her red roadster.

When Hanks was five, living in Redding, California, his parents separated. His mother, a waitress, kept the youngest of the four children while Tom went with the other two to live with his father. He was playing with his siblings one night when he was told he had to go with his father. He was a cook who married twice more and Tom had lots of stepsiblings and lived with a lot of upheaval. “By the age of 10, I’d lived in 10 houses.”

“By and large, they were all positive people and we were all just kind of in this odd pot-luck circumstance,” he says, adding that he still vividly recalls the confusion of being that little boy. “I could probably count on one hand the number of times I was in a room alone with my mum, or in a car alone. That is not exactly what happened to me, but there were times when either my mum or my dad – the same thing was true for both – in which being alone with them, I realised, was like, ‘This is a special time.’ For other people, it’s not a special time. It’s just part and parcel to the day.”

He took Ephron’s advice to heart. His voice is recognisably Hanks, with lots of Norman Rockwell phrasing: “lollygagging”, “yowza”, “thanked his lucky stars”, “titmouse”, “knothead”, “atta baby”.

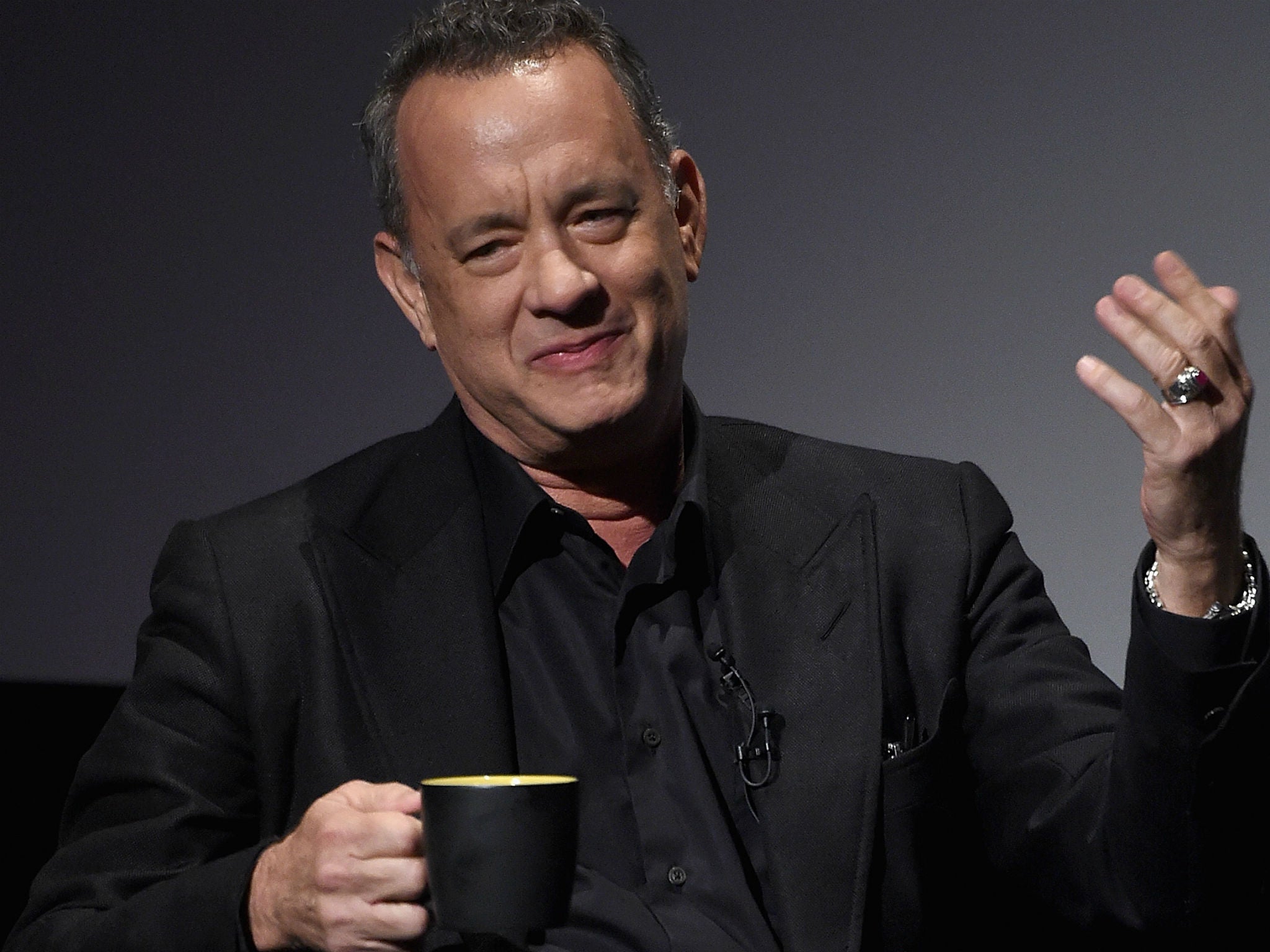

The title of the book is drawn from his love of vintage typewriters. There are 300 or so perched upstairs and downstairs in bookcases in the Santa Monica office of Playtone, his production company, which also boasts a turntable and enviable collection of LPs and 45s. We talk next to rows and rows of rare black and red and green typewriters that do not work but count as “objects of art” for Hanks.

There is also a glamour shot of Ben Bradlee, whom Hanks is portraying in The Post, the upcoming Steven Spielberg-directed movie about The Washington Post’s role in publishing the Pentagon Papers. “Ben knew he was the coolest guy in the room,” Hanks says.

In the adjacent room, bookcases are brimming with covered typewriters. Vintage posters of typewriters hang on the walls.

“Typing was the one requirement my dad had for me, going to school,” Hanks recalls. “He said, ‘goddamn it, you’ll take a typewriting course!’ I think that was the sum total of my dad’s advice to a young man.”

One of his characters in the book, an old-fashioned, tri-cities newspaper columnist, lovingly describes the chonk-chonkka of the keys with the ba-ding of the bell and the krannk of the carriage return and the shripp of the copy ripped from the machine.

He tried to write his fiction on a typewriter but concedes, “I only made it about five pages in.” That delete key on a laptop is too alluring.

All different brands of typewriters – Royals and Remingtons and Continentals – make cameos in the stories, with pictures. It’s “The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog’s” version of Alfred Hitchcock giving himself a walk-on in his movies.

When I ask Hanks how he fell in love with typewriters, he tells the basic story in These Are the Meditations of My Heart, noting, “I changed the gender so they wouldn’t all be about confused young men.” It’s a yarn about a young woman who finds a cheap typewriter at a church-parking-lot sale, goes to a Polish repairman to get it fixed and ends by upgrading to a Swiss sea-foam-green Hermes 2000, the Mercedes of typewriters, with an Epoca typeface.

Did his stint on the early Eighties sitcom Bosom Buddies, in which he dressed in drag, Some Like It Hot-style, to live in an apartment building restricted to women, help him write in a woman’s voice?

“I’m not sure that Lenny Ripps and Chris Thompson wrote in women’s voices per se,” he says with a smile, referring to the show’s writers. “I think between all the women that I worked for and with and gave birth to and married, they all had a great amount of input.”

That character wants a typewriter because her handwriting is so bad. Hanks says that’s his problem, too, that his handwriting is “horrible, horrible”.

He looks at mine and says it’s just as bad, noting: “If you were up for murder, a handwriting expert would read it and say, ‘Oh, she’s guilty, look at the Ys versus the block Js’.”

I am also curious if the futuristic story on time travel, in which a middle-aged man goes back in time and falls in love with a young woman at the 1939 World’s Fair, was inspired by the fortunetelling machine Zoltar in Big.

“No,” he says, “that really came out of a desire to see the 1939 World’s Fair.”

Hanks eats a sushi lunch, casual in Uniqlo jeans, a James Perse black T-shirt, Ralph Lauren boots, a Filson watch with Smokey Bear on it, a David Yurman silver bracelet and a custom-made class ring from the “School of Hard Knocks” with his children’s initials engraved (both pieces of jewellery gifts from his “fabulous wife”). He’s also wearing a dark Lululemon jacket.

“Do not judge me,” he comically instructs. “What happened was that on Sunday, Rita said, ‘Let’s get out of the house.’ I had to buy some workout clothes and we went into Lululemon and I saw this and it kind of fit, so I asked, ‘Is it appropriate for men to wear?’ They said, yeah, so I’m wearing Lululemon.”

He looks trim. “It’s amazing what happens,” he says, “when you finally understand you have Type 2 diabetes and start eating like it.”

I had read that he got diabetes from gaining and losing a lot of weight for roles, but he tells me: “No, I got it from a life of the worst diet on the planet Earth. I just ate sugar and stuff all my life.”

Although he admits he’s not “impervious to perks” – going on private planes is “literally like crack cocaine” – he said he didn’t have any trouble writing about ordinary people beyond the Hollywood bubble.

“Life here is not like The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills,” he says. “No one wears that much lip gloss 24 hours a day or constantly goes out to restaurants only to have arguments about ‘You didn’t invite me to your daughter’s bat mitzvah’.”

When one of his stories, a whimsical tale set in the future about four friends who build a spaceship and fly to the moon – besides typewriters, Hanks has long been obsessed with flying to the moon – appeared in The New Yorker in 2014, a couple of critics pounced. Slate complained that it was “a mediocre story that breezed past the bodyguards because of its Hollywood pedigree” and another writer in The Chicago Tribune, admitting envy, called Hanks “a dabbler at best”.

“Just don’t read the comments because nothing good can come out of it,” he says. “Have you ever had someone say, ‘I read the greatest review of your book,’ or ‘the most glowing review of your movie,’ and you read it and you say, ‘That’s not a glowing review. This guy takes cheap shots left and right and he didn’t get the point.’ Look, I’m 61. I don’t have time to read about how bad or how good I was at something. Just let it sit out there and they have to deal with the fact that I’m the famous guy who got my name in the paper.”

I ask him if he’s going for a “Pegot” (Pulitzer, Emmy, Grammy, Oscar and Tony).

He laughs and says that sometimes you just have to take a risk and be bad at something and get outside yourself and have somebody else critique it and throw stuff away and work harder and that’s how you get better. “I went through some things like, Well, it looks like a piece of writing. It’s on a piece of paper with the right format. And it ain’t.”

As he told The New York Times Book Review, he’s a big reader with stacks of books at home. Does that make him an oddball in Hollywood?

“I think they just assume here you’re a Luddite because the coin of the realm right now is podcasts or obscure shows that are only on for 10 episodes on Hulu or Netflix,” he says. “The dinner party conversation is, ‘I read the most fascinating book about the Civil War’ and they go, ‘Hmm’ and then they move on to some other conversation.”

His favourite book when he was in high school was In Cold Blood, by Truman Capote, but now he prefers Cold War spy stories by Alan Furst and Philip Kerr. He says he’s not interested in murder or conspiracy stories. When he writes, he doesn’t try to get into the head of a psychopath, just a surfer, like himself.

I ask if, as the nation’s designated most likeable actor – even his Halloween monster on Saturday Night Live, David S Pumpkins, is cuddly – he felt pressure to make his fictional characters likable.

“‘Unleash the Charm Monster, damn it, that’s all we want from you,’” he intones in the collective Hollywood voice. But he gets a bit defensive on the issue.

“It’s not a matter of not willing to get dark,” he says. “Look, I played an executioner in a movie. Then the journalist says, ‘Yeah, but you were a nice executioner.’ It wasn’t fun to play a guy whose job it is to put everybody to death. In Road to Perdition, I played a guy who shot people in the head. And you know what they say? ‘Yeah, but you shot him in the head for all the right reasons.’ I’m not interested to play a guy who is some version of ‘Before I kill you, Mr Bond, would you like a tour of my installation?’ I like stories in which everybody makes sense, so you can hear their different motivations and understand them, as opposed to ‘When this elixir goes in the Gotham City water structure, then the city will be mine!’

“I think the best examples of a bad guy that I would jump to be able to play would be Richard III or Iago. I get that. Richard III is this misshapen guy who’s sick of being treated like a dog and he’s got a shot at being the king of England, and Iago lost out on a promotion. But the vast majority of bad guys – what am I going to do, play Loki? No one wants to see me do that. But I could play Jefferson Davis. The biggest thing I have to consider is: what’s my countenance? I don’t have a great deal of mystery.”

Doesn’t he ever want to be like Larry David and start yelling at people on the street? It must be hard when everyone expects you to always be nice.

“I think I am! I’m sorry!” he says, laughing. “I think I give everybody a fair shake. But I will tell you this, and there’s plenty of people who can attest to it, don’t take advantage of my good nature, because the moment that you do, you’re gone, you’re history. I mean, look, I’m not a sap. I’m not naïve. At least I don’t think I am. I understand that part of it is my nature, part of it is my DNA, part of it is the sum total of everything I went through, and it came out OK. But part of it is a choice that just says, how do I want to spend my day? How do I want to spend these hours, pissed off at something or you just kind of let it roll off you. But don’t take advantage of my good nature because if you do, it will come back to haunt you and you will hear from me in no uncertain terms. I’ve yelled at people.” Even used vulgarities.

So now that we’re on the subject of screaming and vulgarities, I segue into the Harvey Weinstein scandal. Talk about a Bonfire of the Vanities, Sherman.

“I’ve never worked with Harvey,” Hanks says, after a long pause. “But, aah, it all just sort of fits, doesn’t it?”

Why did Hollywood help shelter him, if everyone knew about the decades of abusive behaviour?

“Well, that’s a really good question and isn’t it part and parcel to all of society somehow, that people in power get away with this?” he says. “Look, I don’t want to rag on Harvey but so obviously something went down there. You can’t buy, ‘oh, well, I grew up in the Sixties and Seventies and so therefore...” – I did, too. So I think it’s like, well, what do you want from this position of power? I know all kinds of people that just love hitting on, or making the lives of underlings some degree of miserable, because they can.”

They think their achievements entitle them, he says, noting: “Somebody great said this, either Winston Churchill, Immanuel Kant or Oprah: ‘When you become rich and powerful, you become more of what you already are.’

“So I would say, there’s an example of how that’s true. Just because you’re rich and famous and powerful doesn’t mean you aren’t in some ways a big fat ass. Excuse me, take away ‘fat’. But I’m not, you know, I’m not the first person to say Harvey’s a bit of an ass. Poor Harvey – I’m not going to say poor Harvey, Jesus. Isn’t it kind of amazing that it took this long? I’m reading it and I’m thinking ‘You can’t do that to Ashley Judd! Hey, I like her. Don’t do that. That ain’t fair. Not her, come on. Come on!’”

I ask him why Hollywood and Silicon Valley are still such benighted places about women’s rights, with conspiracies of silence about raging sexism and marauding predators.

“Look, I think one of the greatest television shows in the history of television was Mad Men because it had absolutely no nostalgia or affection for its period,” Hanks says. “Those people were screwed up and cruel and mean. And, ‘hey, wait, that’s going on today? Shouldn’t we be on this?’ Is it surprising? No. Is it tragic? Yes. And can you believe it’s happening? I can’t quite believe that” – here Hanks uses an expletive – “still goes on.”

(When I ask about Cam Newton’s gender faux pas, Hanks is more sympathetic. “Now I’ve done that,” he says. “I’m not so far away from ‘Hey, Maureen, how you doing, sweetie?’ ‘Well, look sweetheart.’ ‘Aw, doll baby, I don’t know how to answer that.’ I could have done that in a moment. What’s wrong with having there be a requirement to learn more rules of the workplace?”)

As long as we’re on the subject of Weinstein, a powerful, politically prominent man who got away with bad behaviour toward women for an inexplicably long time, I bring up President Trump.

Hanks says he just listened to the NPR show in which a former producer of The Apprentice admitted that the show made the Trump Taj Mahal in Atlantic City, which was falling apart and, as Hanks says, “stank,” look glossy in an effort to sell the image of Trump, the successful businessman.

“At the time, who cares?” he says. “It’s just a show about a guy. But in retrospect, that is what the official record is of a public figure that holds sway. Making this stuff up is dangerous, man. It’s an absolute, total falsehood.”

He says Trump squeaked through because people were tired of the “Bush-Clinton continuum” for 30 years and political “doublespeak”. He realised, even before the 2016 election, when Joe Wilson yelled “You lie!” at President Obama during an address to Congress, that comity was gone.

I ask Hollywood’s top history buff, the man who sent the White House press corps an espresso machine after Trump’s election because he knew they’d need it (he did this for journalists covering the Bush White House in 2004, too): is this the calm before the storm?

“Let me just read you one thing,” he says, getting up to go into the other room and coming back with April 1865: The Month That Saved America, a book by Jay Winik about the closing weeks of the Civil War: “‘And where abolitionists preached slavery as a violation against the higher law, Southerners angrily countered with their own version of the deity, that it was sanctioned by the Constitution. In the vortex of this debate, once the battle lines were sharply drawn, moderate ground everywhere became hostage to the passions of the two sides. Reason itself had become suspect; mutual tolerance was seen as treachery. Vitriol overcame accommodation. And the slavery issue would not just fade away’.”

He looks up. “Somehow, some time in the last 20 years of our generation, that’s re-emerged. So, yes, this is the calm before the storm.”

I note that he savours the Philip Kerr character Bernie Gunther, a cynical Berlin detective who sees the Nazis for the beasts they are. Is he surprised the Nazis have crawled out of hell, marching in the open in Charlottesville?

“In Germany, in some of the smaller counties, they’ve got Nazis running for office,” Mr. Hanks says. “And jeez, we’ve got Nazis giving torchlight parades in Charlottesville. Don’t you hope that this is just some kind of doomsday fetishism” that will soon die out?

At a tribute to his career last November at the Museum of Modern Art, Hanks gave a soothing Sully Sullenberger-like speech about the election, with the theme “We are going to be all right.” I ask him if he is sure.

He replies that, except for some bone-headed amendments to the Constitution like prohibition – “that was so friggin’ stupid, completely contrary to human behaviour” – America always course-corrects.

“It’s not the first time we’ve had a knot-headed president of the United States,” he says. “We have always corrected something that’s horrible. World War Two was fought by a segregated United States of America, except for a few military units. And immediately after that, it altered. But you have to go through things that will alter the consciousness. And normalcy is always being redefined and you just have to have faith and you have to have some degree of patience and you do have to put up with, every now and again, let’s face it, Nazi torch parades surrounding a phantom issue of a statue that was put up in the 1920s.”

I ask where he stands on the removal of Confederate statues.

“Look, if I’m black and I live in a town and every day I have to walk past a monument to someone who died in a battle in order to keep my grandparents and my great-grandparents illiterate slaves, I got a problem with that statue,” he says. “I would say if you want to be on the safe side, take them all down. Put them in some other place where people can see them, in a museum somewhere.”

Hanks concludes about our rocky road to a more perfect union, “It’s going to be ugly periodically, but it’s also going to be beautiful periodically.” And he advises keeping a sense of humour.

“It might be the only ammunition that is left in order to bring down tyrants,” he says. “You know what Mark Twain says: ‘Against the assault of laughter, nothing can stand’.”

Tom Hanks’s book ‘Uncommon Type’ is published by Penguin on 17 October, £16.99

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments