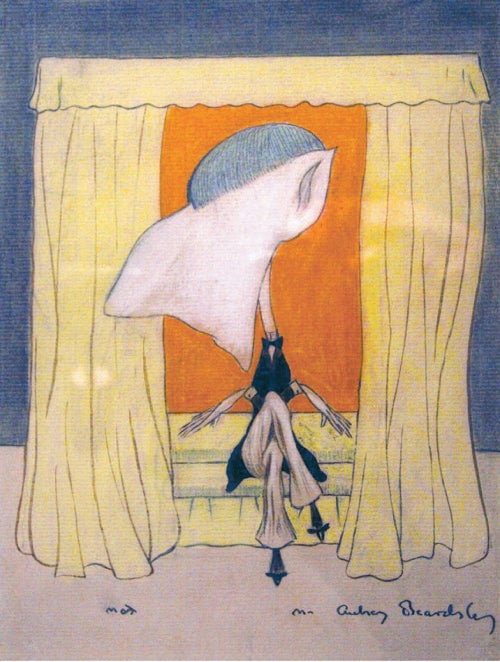

Beerbohm, Max: Mr Aubrey Beardsley (1896)

The Independent's Great Art series

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference. Also in this article:

About the artist

Wittgenstein was talking about how philosophers are led into fruitless perplexity. They ask questions that sound like sensible, answerable questions, but turn out not to be. And he offered this analogy. "Philosophers often behave like little children who scribble some marks on a piece of paper at random and then ask the grown-up 'What's that?' It happened like this: the grown-up had drawn pictures for the child several times and said: 'this is a man', 'this is a house', etc. And then the child makes some marks too and asks: 'what's this then?'"

But never mind about philosophers and little children. What Wittgenstein describes is something that grown-up artists do, and to good effect. It happens like this. The artist builds up an image out of an array of marks, and each of these marks stands for something. But then the code breaks down. The picture contains some marks - not necessarily scribbles - that can't be properly deciphered. They ought to stand for something. You can actually see the representational function they should be performing. But when your eye asks "what's this then?", there is no definite answer. The marks won't read.

This unreadability needn't produce just bafflement. It can be powerfully expressive. One thing it can express, for instance, is a sense of violation. Looking at Goya's massacre-painting, The Third of May, where the face of a dead man is an unreadable mess of paint, Robert Hughes observes: "The wounds that disfigure the face of the man on the ground can't be deciphered fully as wounds, but as signs of trauma embodied in paint they are inexpressibly shocking: their imprecision conveys the sense of something too painful to look at, of the aversion of one's own eyes."

You can't bear to look? That would be one way to understand Goya's failure to depict. But equally it could convey that this face is utterly wiped out, outraged, ruined beyond recognition, defaced - the breakdown of depiction miming the extremity of the damage inflicted. Either way, the very meaninglessness of the strokes acquires a sense, a negative sense. It communicates some kind of loss. The effect is not necessarily horrible, though. In Matisse's drawings, the women's outlines often drift off - for a stretch - into a watery undulation. The pictures carry no anatomical information, but they do convey a body losing itself in a blissful swoon. Or again, unreadability can be used to suggest terminal helplessness.

The youthful caricatures of Max Beerbohm have a merciless eye for weakness. Most caricature is a vivid and even monstrous assertion of the subject's personality. What makes Beerbohm's so intimately lethal is that it touches the spot where personality fails. His victims were almost always known to him personally. His cruelty was to inflict pathos, to insinuate a note of debility. The feeling enters into the drawing itself. Somewhere the line stops being descriptive, wanders off its subject, trails away.

Beerbohm caricatured the illustrator Aubrey Beardsley several times. They were exact contemporaries. The last picture - made two years before Beardsley died of consumption aged 26 - is the most extreme. It shows him as a meagre, dainty, hyper-sensitive figure, limp-wristed and twinkle-toed, with an elfin ear and a monkish fringe that totally obscures his vision. The head as a whole is one of Beerbohm's freest manipulations, distorted almost beyond sense. The face-in-profile is like a fluttering hanky.

There's one particular point where recognition stalls. See what happens between the tip of the nose and the tip of the chin. Both of these points are sharply stressed. But along the outline between them, all angles and information are abolished. This whole stretch of profile - the under-nose, the upper-lip, the mouth, the under lip, the front of the chin - is reduced to a single, gently wavy line.

In Beerbohm's previous caricatures, Beardsley has a rather Easter Island profile, the coastline between nose and chin presented as a succession of sharply cut shelves. But in this version it becomes a shallow tremor. The bridge of the protrusive nose is still well defined. But beneath it, the lower face prolapses. Description fails, and leaves an evacuated area, an unarticulated blur. You can see what it's meant to represent - but follow this contour along, seeking the expected features, and the signal has become hopelessly faint, as if the life of the face was ebbing away.

This is felt most keenly at the mouth. A mouth is always a touchy spot. But in this picture it's barely there, a non-mouth or not-quite-mouth, indicated by a mere gap, a slight break with a slight overlap in this feeble undulation. You can't say what the set of this mouth is, whether it's open or shut. It's rendered in a way that's indecipherable. The just-not-touching, just-overlapping opening creates a frustrating vagueness. You want the gap to close, the lines to meet, to form something clear and readable, to de-fine a nice prim little mouth. But they won't.

It is a fearful defacement - and all the more so because you can see it, not as something done to the figure, but as something the figure is doing itself. This failure of facial definition seems to be in character. It fits in with the personality of Beardsley, as established by the rest of the caricature. Its vagueness looks like an aspect of the figure's own exquisite refinement and sensitivity, a further expression of the fastidious tentativeness so evident already in its body language.

In other words, Beerbohm implies, this is exactly the kind of profile that this dandyish aesthete would make for himself. This is his own ideal face. The standard cut-and-thrust of nose and lips - my dear! nothing so crude, so vulgar, so physical. The face's ins and outs are to be registered as a barely fluid motion, a flicker, the merest nuance, something quite indefinable; the physiognomy as je ne sais quoi. Caricature doesn't get more insidious, more inside.

Max Beerbohm (1872-1956) was an essayist, parodist, critic, cartoonist and man-about-town. His literary parodies are simply the best ever. As a cartoonist he was an amateur of genius. He borrowed the style of the Victorian Vanity Fair caricaturists, with their sharp sense of pose and social presence, and infused it with the flaccid helplessness of Edward Lear's nonsense drawings. He specialised in his contemporaries in art and letters. He knew them inside out, and they knew it. When Henry James, one of his favourite subjects, was asked his opinion on something at a dinner party, he pointed to Beerbohm: "Ask that young man, he is in full possession of my innermost thoughts."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments